When you first press play on Giuseppe Bonaccorso’s “Playground in Gaza,” something quietly unsettles you. The opening notes seem almost fragile—delicate enough to break if you touch them—but they carry a weight that lingers in the air. Slowly, like colors bleeding into water, the music changes. Warm tones grow colder. Familiar shapes bend out of recognition. And then you realize: this is no ordinary instrumental piece.

“Playground in Gaza” feels less like a composition and more like a place—one you walk through cautiously, unsure what you’ll find around each corner. It’s a place where children’s laughter has long since faded, replaced by an uneasy silence, and where every stone bears the mark of a story you wish you didn’t have to hear.

From his roots in Italy—shaped by both the arts and a deep intellectual curiosity—Giuseppe Bonaccorso pursued music that challenges rather than soothes, music that refuses to sit still in comfortable categories. His style is fiercely personal, born of a belief that sound can capture emotions words often miss entirely.

In “Playground in Gaza,” that belief is on full display. It’s not a song that offers simple melodies or easy rewards. Instead, it draws you in with something almost deceptively calm, then slowly begins to strip away the comfort. Notes twist into new, uneasy shapes. Harmonies that began as safe and steady begin to fracture. It’s as if the music itself is losing its sense of home.

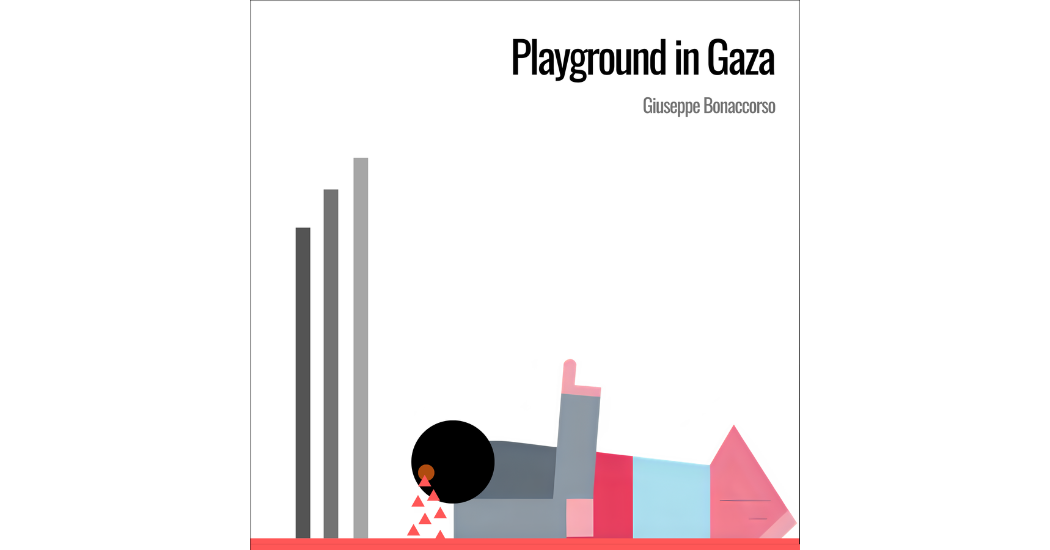

And that’s the point. Bonaccorso has described the piece as the transformation of something “normal” into something distorted—an intentional musical reflection of life under siege. In Gaza, even the most ordinary things—streets, homes, playgrounds—are not safe from destruction. The sound is both mourning and a protest.

What makes the piece so powerful is that it never becomes melodramatic. The sorrow is there, yes, but it’s held with a kind of dignity. The track listens as much as it speaks; it feels like an act of witness. You absorb it, as if some part of the tension and weariness of a faraway place has been transferred into your own body.

There’s history in this kind of art. For centuries, composers have responded to human suffering with works that try to catch the uncatchable, to give form to grief and resilience. Bonaccorso’s piece steps into that tradition without imitation. It belongs to this moment, yet it echoes a long lineage of artists who understood that music can outlast the very events it mourns.

Of course, no track can bear the weight of a political crisis on its own. But sometimes, music doesn’t have to solve anything to matter. Sometimes, it matters simply because it refuses to look away. If music can carry the voices of those who cannot speak for themselves… How much longer can the world pretend not to hear?

View this post on Instagram